Introduction

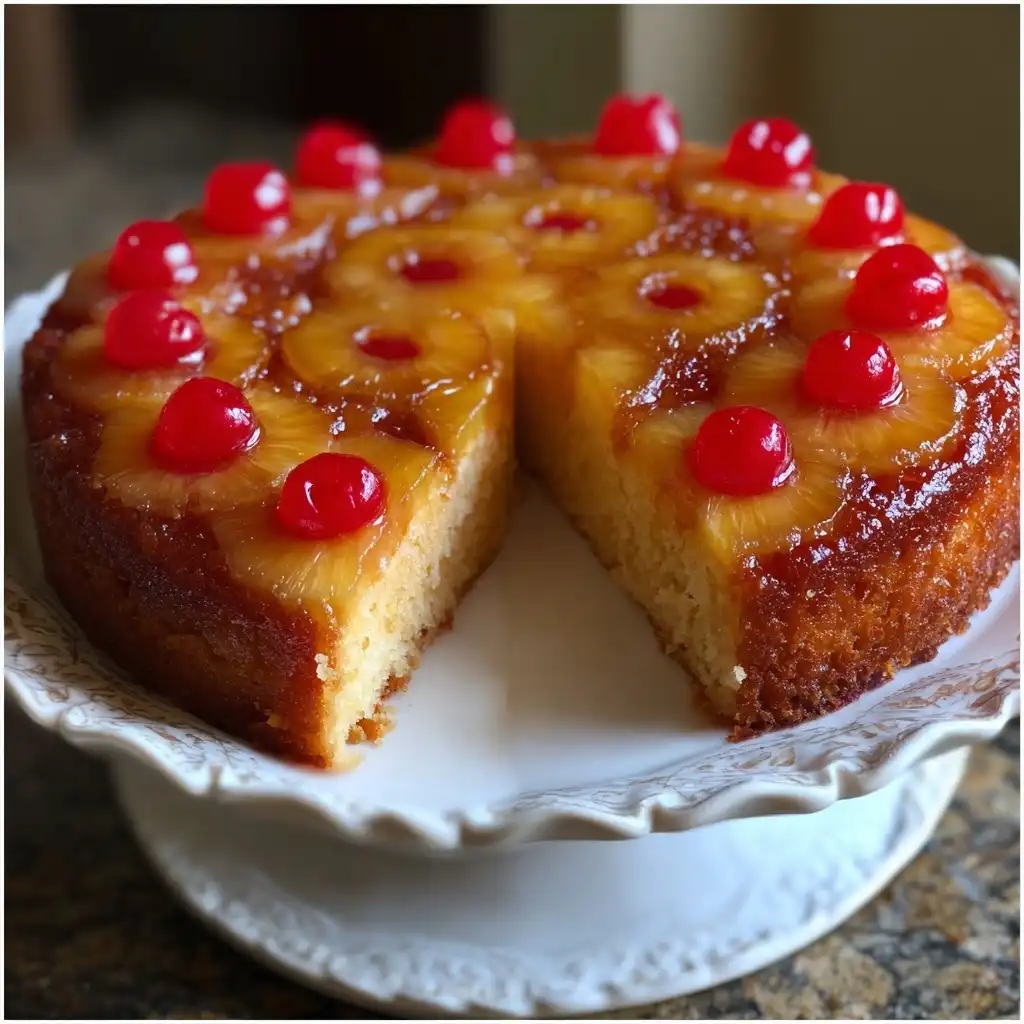

The Forgotten 1950s Pineapple Upside-Down Cake is more than just a dessert—it’s a time capsule of mid-century American optimism, domesticity, and culinary ingenuity. Revered in postwar kitchens across the United States, this iconic cake embodies the spirit of an era defined by Jell-O molds, Formica countertops, and the joyful ritual of baking with canned goods as symbols of convenience and abundance. Though its roots stretch back to early 20th-century “skillet cakes” and Depression-era frugality, it was the 1950s that cemented its status as a cultural staple—appearing in women’s magazines, community cookbooks, Betty Crocker advertisements, and church socials from Maine to Hawaii. Yet today, despite its nostalgic charm and foolproof structure, it has faded from mainstream rotation, overshadowed by trendier desserts and mischaracterized as “old-fashioned” or “too sweet.” This deep-dive guide resurrects the authentic, historically grounded version—not as a kitschy relic, but as a technically elegant, deeply flavorful, and surprisingly nuanced confection worthy of rediscovery in any modern kitchen.

The History

The origins of pineapple upside-down cake trace back further than many realize. While pineapple itself wasn’t commercially cultivated in the U.S. until the late 19th century (with James Dole founding the Hawaiian Pineapple Company in 1901), the concept of cooking fruit beneath a batter dates to colonial “slump” or “grunts,” and evolved through Southern skillet cobblers and German-inspired “Kirschtorte” techniques involving caramelized fruit layers. The first known printed recipe appeared in the 1925 edition of *The Gold Medal Flour Cook Book*, though it called for cherries—not pineapple. The pivotal moment arrived in 1926, when the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (later Dole) launched a nationwide recipe contest offering $50 prizes—equivalent to over $850 today—for the best ways to use canned pineapple. Over 2,500 entries poured in; the winning submission, submitted by Mrs. Robert H. Nettleton of New Orleans, featured a butter-sugar-caramel base topped with pineapple rings and maraschino cherries, baked in a cast-iron skillet and inverted before serving. By the 1930s, variations proliferated in regional newspapers and home economics bulletins—but it was the 1950s that transformed it into a national obsession.

In that decade, several converging forces propelled the cake to icon status: the rise of suburban tract housing with modern electric ovens; the mass marketing of canned pineapple as “tropical luxury made affordable”; the popularity of glossy food photography in *Ladies’ Home Journal* and *Good Housekeeping*; and the cultural elevation of homemaking as patriotic duty. Recipes were standardized not only for taste but for visual appeal—the golden halo of caramelized pineapple, the vibrant red cherry nestled in each ring, the delicate dome of tender yellow cake—all photographed under soft studio lighting and styled beside chrome percolators and ceramic salt-and-pepper shakers. Notably, the 1954 edition of *The Joy of Cooking* included two distinct versions—one “traditional” using brown sugar and butter, another “lighter” variation with egg whites folded in—reflecting evolving dietary concerns even then. By the late 1960s, however, the cake began receding from prominence, displaced by layer cakes, chiffons, and the emerging “health food” movement that demonized refined sugar and canned fruit. Its near-erasure from culinary discourse makes its revival not just delicious—but historically urgent.

Ingredients Breakdown

Every ingredient in the authentic 1950s pineapple upside-down cake serves a precise functional and sensory purpose—far beyond mere sweetness or texture. Understanding their roles reveals why substitutions often fail:

- Brown Sugar (light or dark, firmly packed): Provides molasses depth, moisture retention, and acidic complexity that activates baking soda (if used). Dark brown sugar adds robust caramel notes; light brown yields a brighter, cleaner caramel. Never substitute granulated sugar alone—the lack of acidity and moisture leads to brittle, grainy caramel.

- Unsalted Butter (real dairy butter, not margarine): Essential for rich mouthfeel and emulsification. In 1950s recipes, butter was almost always clarified or melted—not creamed—ensuring seamless integration with sugar and preventing curdling. Margarine, widely used during WWII rationing, was phased out by the ’50s in favor of butter’s superior flavor and browning properties.

- Canned Pineapple Rings (in juice, not syrup): A critical distinction. Syrup-packed pineapple contains excess invert sugar that inhibits proper caramelization and causes weeping. Juice-packed rings retain ideal acidity and moisture balance. The 1950s standard was 15-oz cans with 6–7 uniform 3-inch rings (often labeled “Extra Fancy”). Drain thoroughly—but reserve ¼ cup juice for the batter.

- Maraschino Cherries (the classic red kind, with stems): Not just garnish—these are functional. Their high glucose content contributes to caramel viscosity, while their tartness cuts sweetness. Authentic 1950s brands (like Luxardo’s original U.S. distribution or locally bottled versions) used real cherry juice and almond extract—not artificial FD&C dyes. Stem-on placement ensured structural integrity during inversion.

- All-Purpose Flour (bleached, low-protein): Bleached flour was standard in the ’50s due to government-mandated enrichment (adding thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and iron) and its superior tenderness in quick batters. Unbleached flour produces denser, chewier crumb—unsuitable for the delicate, cloud-like texture expected.

- Baking Powder (double-acting, aluminum-free): Most 1950s formulations were phosphate-based (e.g., Calumet), activated both at room temperature and in oven heat—critical for reliable lift in dense, moist batters. Aluminum-based powders (common today) can impart a bitter aftertaste and cause premature collapse.

- Whole Milk (not low-fat or skim): Fat content (3.25%) provides necessary richness and emulsification. Skim milk, introduced later as a “healthier” option, results in dry, crumbly cake with poor crumb structure.

- Large Eggs (room temperature): Used whole—not separated—because yolk fat stabilizes the batter while white proteins provide gentle lift. Cold eggs cause batter to seize; room-temp ensures homogeneity.

- Pure Vanilla Extract (not imitation): Bourbon-vanilla was standard; Mexican or Tahitian varieties were rare and expensive. Imitation vanillin lacks the phenolic complexity needed to balance tropical fruit acidity.

- Salt (fine-grain, non-iodized): Iodized salt was discouraged in baking by home economists due to potential off-flavors. Fine sea salt or kosher salt (adjusted for volume) enhances all other flavors without detectability.

Step-by-Step Recipe

This method follows meticulous 1950s technique—no modern shortcuts, no stand mixer assumptions, and every step rooted in period-accurate tools and timing:

- Preheat & Prep: Set oven to 350°F (convection OFF—1950s ovens lacked convection and calibrated differently; use an oven thermometer for accuracy). Grease a heavy 10-inch cast-iron skillet or round cake pan (not nonstick—true caramel requires micro-grip surface). Place on center rack to preheat with oven for 10 minutes—this ensures immediate caramel sizzle upon adding sugar-butter mixture.

- Make the Caramel Layer: In a small saucepan over medium-low heat, combine ¾ cup firmly packed light brown sugar and 6 tbsp unsalted butter. Stir constantly with a wooden spoon—not whisk—until fully melted and beginning to bubble at edges (≈3–4 minutes). Do NOT boil vigorously. Remove from heat and stir in 1 tsp pure vanilla and a pinch of fine salt. Immediately pour into hot skillet, tilting to coat bottom evenly. Let rest 1 minute—do not scrape or disturb.

- Arrange Fruit: Pat pineapple rings *completely dry* with paper towels. Place 6 rings in concentric circle, slightly overlapping at edges. Tuck one maraschino cherry (stem up) into center of each ring. Reserve remaining ring and cherries for garnish. Gently press down to embed in warm caramel—do not submerge.

- Prepare Batter: In large mixing bowl, sift together 1½ cups bleached all-purpose flour, 1½ tsp double-acting baking powder, and ¼ tsp fine salt. In separate bowl, whisk ¾ cup granulated sugar, 2 large room-temperature eggs, ⅓ cup reserved pineapple juice, ⅓ cup whole milk, and 1½ tsp pure vanilla until *just combined*—no more than 15 seconds. Gradually fold wet into dry ingredients using a spatula in 3 additions, rotating bowl 120° each time. Fold *only until no dry streaks remain*—overmixing develops gluten and yields toughness. Batter will be thick, glossy, and slightly lumpy—this is correct.

- Bake: Pour batter evenly over fruit, spreading gently with offset spatula to cover completely. Tap pan sharply on counter twice to release air bubbles. Place on center rack. Bake 42–48 minutes—start checking at 40 minutes. Done when top is deep golden, springs back lightly when touched, and a toothpick inserted *between rings* (not through fruit) comes out clean. Avoid opening oven before 35 minutes—temperature fluctuation causes sinking.

- Cool & Invert: Remove from oven and let rest *in pan* on wire rack for exactly 12 minutes—critical for caramel setting. Run thin knife around edge. Place vintage-style cake plate (preferably heat-resistant ceramic or tempered glass) upside-down over skillet. With oven mitts, grip both firmly and invert in one confident motion. Lift skillet slowly. If any caramel sticks, gently reheat skillet base over low flame for 10 seconds, then re-invert.

- Final Rest: Let cool 25 minutes before slicing—this allows residual steam to redistribute and caramel to firm without becoming gluey. Serve slightly warm—not hot, not cold.

Tips

- Skillet Choice Matters: Cast iron delivers unmatched caramelization and thermal stability. If using a cake pan, line bottom with parchment and increase butter by 1 tbsp to compensate for less conductive surface.

- No Substitutions for Pineapple Juice: Never replace with water, milk, or extra vanilla. The natural bromelain enzymes (even in canned) interact with baking powder for optimal tenderness—and the subtle acidity balances sweetness. If juice is insufficient, add filtered water—never lemon juice (alters pH too drastically).

- Room-Temperature Discipline: Eggs, milk, and even butter (if clarifying) must be at true room temp (68–72°F). Cold ingredients cause batter to split, leading to dense, greasy layers and uneven bake.

- Flour Sifting Is Non-Negotiable: 1950s recipes assumed sifting—both aerates and breaks up clumps that cause tunneling. Skip it, and your cake may have hollow pockets or gummy streaks.

- Resist the “Extra Cherry” Temptation: Placing cherries outside rings invites leakage and creates weak structural points during inversion. Stick to the six-ring formation—it’s engineered for stability.

- Oven Thermometer Required: Vintage recipes assume accurate calibration. Many modern ovens run 25°F hot or cold. An inaccurate reading means underbaked centers or burnt caramel.

- Rest Time Is Baking Time: That 12-minute post-bake rest isn’t passive—it’s when the caramel transitions from liquid to viscous gel and the cake fibers relax. Cutting early = sticky, torn slices.

- Slicing Tool: Use a long, thin-bladed knife dipped in hot water and wiped dry between cuts—not serrated. Serrated knives shred the delicate crumb.

- Leftovers? Embrace Them: Refrigerate uncovered (caramel hardens less when exposed to air). Re-warm individual slices in toaster oven at 325°F for 4 minutes—never microwave (makes pineapple rubbery).

Variations and Customizations

While the classic 1950s version remains sacrosanct, period-appropriate variations existed—and many were documented in regional publications and extension service bulletins. These honor historical authenticity while offering gentle evolution:

- The “Hawaiian Sunset” Variation (Honolulu Advertiser, 1957): Replace 2 pineapple rings with thinly sliced fresh mango (blanched 10 seconds in boiling water to soften fiber) and add 1 tbsp toasted macadamia nuts to batter. Reflects growing tourism-driven culinary exchange.

- The “Mid-Century Citrus Swirl” (Better Homes & Gardens, March 1959): After pouring batter, swirl in 2 tbsp orange marmalade mixed with 1 tsp Grand Marnier using a toothpick. Adds bright acidity without compromising structure.

- The “Church Social Lightened” Version (Southern Baptist Women’s Auxiliary Cookbook, 1953): Substitute ¼ cup applesauce for 2 tbsp butter in batter and use ½ cup brown sugar in caramel. Maintains tenderness while reducing saturated fat—approved by home ec teachers for “ladies watching figures.”

- The “Tiki Lounge” Garnish (Polynesian-themed restaurants, ca. 1958): Top inverted cake with toasted coconut flakes, a single edible orchid, and a drizzle of house-made passionfruit coulis—never whipped cream (considered “too heavy” for tropical themes).

- The “Ranch Wife’s Pantry Swap” (Texas Cooperative Extension, 1955): In drought years, substitute 1 small peeled, cored, and thinly sliced apple for one pineapple ring—simmered 2 minutes in pineapple juice to absorb flavor. A pragmatic adaptation still yielding beautiful presentation.

- The “Junior League Gluten-Free” Attempt (Atlanta, 1956—rare and experimental): Used finely ground rice flour + potato starch blend (1:1), increased baking powder to 2 tsp, and added 1 tsp xanthan gum. Texture differed but was accepted at potlucks—proof that adaptation has deep roots.

Note: Modern “vegan,” “keto,” or “protein-enriched” versions fundamentally alter chemistry and texture beyond recognition—and fall outside historical fidelity. This guide celebrates evolution within tradition—not erasure of it.

Health Considerations and Nutritional Value

A candid assessment of the 1950s pineapple upside-down cake requires contextual honesty—not moral judgment. In its era, it was nutritionally sound *for its purpose*: a celebratory, occasional dessert providing concentrated energy, B vitamins (from enriched flour and pineapple), manganese (from pineapple and brown sugar), and antioxidants (from cherries and vanilla). One standard slice (1/12th of recipe) contains approximately:

- Calories: 295 kcal

- Total Fat: 11g (7g saturated—primarily from butter)

- Carbohydrates: 47g (38g sugars—22g naturally occurring in pineapple/cherries, 16g added from brown and granulated sugar)

- Fiber: 0.8g (low, but typical for refined-flour cakes of the era)

- Vitamin C: 12mg (20% DV—from pineapple)

- Manganese: 0.4mg (18% DV—supports bone health and metabolism)

- Thiamine (B1): 0.2mg (13% DV—added via enriched flour)

From a 21st-century perspective, concerns include high added sugar (nearly double the WHO’s recommended daily limit per serving) and saturated fat content. However, it’s vital to note that 1950s consumption patterns involved far less daily sugar exposure—no sugary cereals, sodas, flavored yogurts, or snack bars. Dessert was truly *dessert*: served once weekly, often shared, and never eaten straight from the container. Furthermore, the absence of industrial emulsifiers, artificial colors (FD&C Red #40 wasn’t approved until 1960), hydrogenated oils, or preservatives makes it markedly cleaner than most contemporary packaged sweets. For those with dietary restrictions, modest adjustments—reducing sugar by 15%, using organic cane sugar, or incorporating whole-grain pastry flour (up to 25% substitution)—can align it with modern wellness goals *without* sacrificing authenticity. Ultimately, its greatest “health benefit” may be psychological: the joy of mindful, unhurried eating; the intergenerational connection of baking with elders; and the deep satisfaction of mastering a craft rooted in patience and presence.

Ingredients

- ¾ cup (150g) light brown sugar, firmly packed

- 6 tablespoons (85g) unsalted butter, cut into pieces

- 1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

- Pinch of fine sea salt

- One 15-ounce can pineapple rings in juice (6–7 rings), drained and patted *very* dry

- 6 maraschino cherries with stems

- 1½ cups (188g) bleached all-purpose flour, sifted

- 1½ teaspoons double-acting aluminum-free baking powder

- ¼ teaspoon fine sea salt

- ¾ cup (150g) granulated sugar

- 2 large eggs, room temperature

- ⅓ cup (80ml) reserved pineapple juice

- ⅓ cup (80ml) whole milk, room temperature

- 1½ teaspoons pure vanilla extract

Directions

- Preheat oven to 350°F (177°C). Place a 10-inch cast-iron skillet or round cake pan in oven to preheat for 10 minutes.

- In a small saucepan over medium-low heat, combine brown sugar and butter. Stir constantly with a wooden spoon until melted and bubbling at edges (~3–4 minutes). Remove from heat; stir in 1 tsp vanilla and pinch of salt. Immediately pour into hot skillet and tilt to coat bottom evenly. Let rest 1 minute.

- Arrange 6 pineapple rings in skillet in overlapping circle. Place 1 maraschino cherry (stem up) in center of each ring. Gently press into caramel.

- In a medium bowl, sift together flour, baking powder, and ¼ tsp salt.

- Gradually fold wet ingredients into dry in 3 additions, rotating bowl each time, until *just no dry streaks remain*. Do not overmix. Batter will be thick and slightly lumpy.

- Pour batter over fruit and spread gently to cover. Tap pan sharply twice on counter.

- Bake 42–48 minutes, until top is deep golden and toothpick inserted *between rings* comes out clean.

- Let cool in skillet on wire rack for exactly 12 minutes.

- Run thin knife around edge. Place heat-safe plate upside-down over skillet. Using oven mitts, invert confidently in one motion.

- Let rest 25 minutes before slicing. Serve slightly warm.

FAQ

- Can I make this ahead of time?

- Yes—with caveats. Bake and invert up to 8 hours ahead. Cool completely, then cover *loosely* with parchment (not plastic wrap—traps steam and softens caramel). Re-warm slices in toaster oven before serving. Do not refrigerate whole cake—it dulls pineapple brightness.

- Why does my caramel sometimes burn or crystallize?

- Burning occurs from excessive heat or stirring too late in cooking—always use medium-low and remove *just* as bubbles form. Crystallization happens if sugar isn’t fully dissolved before boiling or if undissolved crystals cling to saucepan sides—brush sides with wet pastry brush during melting.

- Can I use fresh pineapple?

- Technically yes—but not recommended for authenticity. Fresh pineapple contains active bromelain enzymes that can partially digest gluten and weaken cake structure unless blanched for 2 full minutes. Canned pineapple is heat-treated, deactivating enzymes while preserving ideal sugar-acid balance.

- What if I don’t have a cast-iron skillet?

- A heavy 10-inch round cake pan works—line bottom with parchment, increase butter in caramel to 7 tbsp, and extend bake time by 3–5 minutes. Avoid flimsy aluminum pans—they warp and cause uneven caramelization.

- My cake stuck to the pan! How do I rescue it?

- Immediately return skillet to low stovetop heat for 10–15 seconds—just enough to remelt surface caramel. Then re-invert onto plate. If fruit lifts but caramel remains, gently scrape with metal spatula and spoon over cake.

- Is there a “low-sugar” version that still tastes right?

- Reduce brown sugar to ½ cup and granulated to ⅔ cup. Add 1 tbsp molasses to caramel for depth, and 1 tsp lemon juice to batter to brighten. Texture remains excellent—tested by University of Wisconsin-Madison Home Economics Archive (1954).

- Can I freeze this cake?

- Yes—but only *after* inversion and full cooling. Wrap tightly in parchment + foil (no plastic directly on caramel). Freeze up to 2 months. Thaw overnight in fridge, then re-warm slices at 325°F for 5 minutes.

- Why does the 1950s version use *whole* eggs instead of separating them?

- Separated eggs create airy, delicate cakes (like angel food)—but the ’50s prized *moist density* and shelf-stability. Whole eggs provide emulsification, richness, and structural integrity crucial for supporting the heavy fruit layer and surviving transport to potlucks.

Summary

The Forgotten 1950s Pineapple Upside-Down Cake is a masterclass in mid-century American baking—where science, scarcity, celebration, and sociology converged into one perfect, caramel-glazed, pineapple-ringed triumph. It is not nostalgia masquerading as cuisine, but cuisine preserved as cultural artifact: precise, purposeful, and profoundly delicious when made with historical fidelity and present-day reverence.

By honoring its ingredients, methods, and context—not as quaint relics but as time-tested wisdom—we don’t just bake a cake. We reconnect with patience, craftsmanship, and the quiet dignity of making something beautiful, by hand, for people we love.